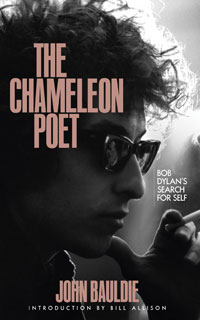

Bill Allison and John Bauldie, 1980s

The Chameleon Poet manuscript came to us via John Bauldie’s lifelong friend, Bill Allison. During the process of preparing the manuscript for publication, we spent many hours with Bill who regaled us with countless stories about John, providing invaluable context. The book is objectively a critical study of Bob Dylan’s work, and as such is thoroughly conceived, but such accounts are never free of personal responses to the work so it was important for us to understand the man in order to fully understand his text. Some of the stories Bill told us about John’s life are recounted in the introduction he wrote to the book, but there was nothing in there on the provenance of the manuscript, and where it had been resting for the past 40 years, so we invited Bill to write a little about that for us. Here’s the story he sent.

——————————————————————————————————————————————–

I would like write about how the manuscript for The Chameleon Poet was found hidden in a terracotta jar in a cave near a desert, stuffed behind some rather large canvases in a Bloomsbury attic, in a bunker of looted war treasure or in an old dusty university library. I can’t. The manuscript for The Chameleon Poet has sat in a steel trunk in my attic for twenty-five years. The most exotic its storage gets is that the trunk was commissioned by my grandad on his return from India in 1932. It’s emblazoned with an inscription on the lock which tells that it was made in Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, the home of the best locks in the world. Nevertheless, the manuscript’s preservation has been just as important to the world of Dylan Studies as any of the above have been respective to theirs.

People who recognise the name of John Bauldie will perhaps be aware of something of his biography, his life and his death, which I describe in my extended introduction to The Chameleon Poet. In there I have deliberately avoided telling the story of where the manuscript has been. But for those who want to know, here it is.

Film directors are known to issue the command ‘Cut on action’. This is all well and good but there will obviously be footage that spills off the reel and falls on the cutting room floor. Rather cliché ridden I know. However, when a person’s life is cut on action, especially before its rightful time, the very same happens. Very few are ready for death, certainly when death occurs to the young, nothing is in order, nothing is finished, nothing is closed.

When John died in October 1996, Penny, his partner of over twenty-five years, asked me to take everything away, take care of it and look to any unfinished business. So, after his funeral, boxes and boxes of newspaper cuttings, magazines, posters, books and tapes filled my car and made its way from Richmond upon Thames to my home in Lancashire. All of it went into my attic, that Aladdin’s cave of a lifetime’s junk.

Rather tragically Penny, who was John’s literary executor, died in 2004. Penny and I had been close friends since 1975 and knew the intimacies of each other’s lives. We were always in touch until her death. The literary estate then passed to Penny’s sister, Margaret, who felt the same as Penny about John’s work and suggested I carry on with what Penny had asked me to do.

Everyone’s first concerns were the tapes. What was in John’s fabled Dylan tape collection? Would we find acetates of ‘Church with No Upstairs’ or ‘Snow on the Interstate’? Would there be music that collectors would drool over?

Well actually, no. John was generous to a fault and always gave copies of whatever he had to close friends who would pass copies on to their close friends until everyone who wanted it had it and had already drooled over it. And actually, don’t hold your breath, as far as we know the two tracks listed above don’t exist. Myth becomes fable becomes history but they were just figments of tape hungry, scoop needy journalists’ imagination.

John’s collection contained recordings in every format available from 1965 onward. So there were stacks and stacks of open reel tapes, box after box of cassettes and the beginnings of a CD-R stash.

His CD-Rs weren’t as extensive as they might have been since John felt that DATs offered a better quality sound and he was in the process of transferring some of his collection to DAT.

For fifteen years this hoard rested in our house above our heads, piled in amongst the Christmas decorations, outgrown children’s toys and old lamp shades that had gone out of fashion as I continued to work as a senior leader in secondary school. I retired in 2010. My daughters who were massive Dr Who fans at the time suggested that I hadn’t retired, an awful concept, but that I had regenerated and indeed such was the case.

Upon regenerating there were certain things that I felt that I had to do. John always said that there were people and there was stuff, and that people were more important than stuff. However to do right by John, I felt that I had to sort his stuff out. This was top of my ‘to do’ list. So I began to trawl and this took some considerable time. Months running to years.

The boxes of tapes got in the way of everything. I constantly fell over them whenever I went up into the attic. They hindered getting the Christmas decorations out, climbing over them for fifteen years or so. I toyed with the idea of listing them, playing them all to check what was there and if indeed there were any surprises. Collectors and I were in touch. The quest was always to try and find better quality recordings that were closer to the source tape. Indeed over the years I had played my own part in the world of ‘Dylan Collecting’. Like John, I was a grown man from the North of England who had started collecting Dylan tapes as a seemingly little boy and swapping them as if I was a bright-eyed schoolboy swapping stamps to put in my album. Still, I quite quickly came to the conclusion that the tapes of Dylan’s music held nothing to reveal that we didn’t already know about.

Next up was the paperwork, and there was lots of it. Original newspaper cuttings about the 1966 havoc-wreaking world tour, reviews of the comeback tour in 1974, and photographs of the 1975 Rolling Thunder Tour amongst much, much more. Then The Telegraphs. Cut and paste starting-point copies of many issues, culminating in all published fifty-six editions, most with beautiful colour photographs on the front.

Amongst the material were also ring-binder folders of various sizes. Some contained handwritten material and some had what was in them typed up. I actually found it emotionally quite difficult to look into these and put it off for some time as I tried to make sense of my feelings. These days we are told that it is good thing for men to articulate their emotions and even cry if necessary. But this didn’t seem to be the case then. as recently as 2010. It was Margaret who attempted to articulate for me what I was feeling. She suggested that even now I was still grieving for John, someone who had played a massive part in my life. Our lives had been as tangled as spaghetti. For a quarter of a century we had seen each other’s ups and downs, highs and lows and blues.

Amongst the material were also ring-binder folders of various sizes. Some contained handwritten material and some had what was in them typed up. I actually found it emotionally quite difficult to look into these and put it off for some time as I tried to make sense of my feelings. These days we are told that it is good thing for men to articulate their emotions and even cry if necessary. But this didn’t seem to be the case then. as recently as 2010. It was Margaret who attempted to articulate for me what I was feeling. She suggested that even now I was still grieving for John, someone who had played a massive part in my life. Our lives had been as tangled as spaghetti. For a quarter of a century we had seen each other’s ups and downs, highs and lows and blues.

Eventually I began to look at what was inside the files. Quite quickly it became clear that they all contained the same material, albeit with different working titles, written by hand or typed. They were versions of what John had called The Chameleon Poet: Bob Dylan’s Search for Self 1962-1980. Clearly I knew of the manuscript. I had read a version long ago when he was working on it. I had discussed with him the ideas he explored in it. He had often referred to it, albeit tongue in cheek, in The Telegraph, had published one chapter in a Dylan fanzine and later another in The Telegraph. So, although it sounds rather dramatic, I had in my hand what I would consider to be John Bauldie’s unpublished magnum opus. Not quite The Dead Sea Scrolls but, nevertheless, as important to the world of Dylan Studies in understanding and appreciatingDylan’s work as The Scrolls were to understanding and appreciating First Century BCE Judaism.

Somehow, out of deep seated loyalty to John and my appreciation of what the work offered, I became determined to have The Chameleon Poet published. In the period since John’s death, his name and what he did vis-à-vis The Telegraph and his involvement in the The Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3 were continually mentioned, so it seemed to me that the world needed to see his major work and then John Bauldie would perhaps receive his rightful place at what I have called the high table of Dylan Studies. John’s quest, his challenge, had been to bring to the world the notion that Dylan’s work could be written about in the same way that Shakespeare’s, Keats, Dickens or any other major writer you care to mention could be. In fact as early as 1990 he had led the idea that Dylan’s name should be forwarded to the Nobel Prize Committee to be recognised as someune who should be awarded their Prize for Literature.

Despite all his achievements, John had never published anything of his own about Dylan’s work in mainstream publishing. He had written more than sixty-five articles for The Telegraph. He had co-edited a book of articles of his own and others from The Telegraph and followed this up with a second collection from its pages of interviews with those who had worked creatively with Dylan. Finally, just before his death, he published a book he worked on with journalist Patrick Humphries.

I discussed the idea of publication with Margaret who felt it was an important idea and suggested I go ahead. I asked close friends and some of the original Wanted Men to read the manuscript and offer thoughts. At the same time I read and reread the book until I was more than familiar with it, never doubting its importance.

So then I turned my attention to its publication and this proved to be illuminating. For someone who had been very successful in his own world to then dip his toes into another where he had no experience was not easy. Where do you begin?

I approached firms that had published the books John had co-edited with little response. I approached companies it was suggested to me might be interested. I approached those that specialised in publishing books about rock music. All to little or no avail.

It was pointed out time and time again that the book had little or no potential to make money. Somebody actually said to me in a phone call that the problem would be that John wasn’t alive to do interviews about the book. So that should see the end of republications of books by C.S. Lewis and Professor Tolkien amongst a multitude of other inklings shouldn’t it?

Despite the setbacks, I never gave up on the idea because I had faith in the book, but I did perhaps start to lack faith in my own ability to open the door. Still, one often reads about major works that had been rejected by publisher after publisher so I was still a believer.

Then a kind of coincidental symbiosis took over. In May 2017 I was in Pontefract with Clinton Heylin who had invited me to a talk he was giving at The CAT Club there. Before the talk he took me to the house of Ian Daley and Isabel Galán where, rather embarrassingly, I hadn’t realised that Ian and Isabel were owners and publishers of Route Books. I still blame that on Clinton for not telling me that Route published some of his material about Dylan. I blame Clinton for a lot of things.

The conversation turned to Dylan. Clinton told Ian I had been a friend of John Bauldie. He asked about John. It turned out that he was a fan of John’s too so to speak, that he’d been a subscriber to The Telegraph, and waxed lyrical about how he had once stood next to John at a Dylan concert in 1987.

I dropped into conversation that I had the manuscript of John’s The Chameleon Poet that I was looking to get published. Ian asked to look at it and quite quickly realised its importance and wanted to publish it. The rest, as they say, is history…

Bill Allison

January 2021.

Click here for more on The Chameleon Poet: Bob Dylan’s Search For Self.